During the fourth week, work on the key themes of Reformed confessional culture that began the previous week continued. On Monday, Anne Käfer, a professor at the University of Münster, presented an initial systematic reflection on the doctrine of predestination. Then, together with the course participants, she read important sources from Luther’s “On the Bondage of the Will,” the Augsburg Confession, the 39 Articles, and the Formula of Concord up to the decisions of the Synod of Dort.

It became clear that Luther’s views on predestination and election were similar to those of the Reformed churches of the 16th and early 17th centuries. Early modern Lutheranism did not emphasize this doctrine but rather interpreted it differently, referring to faith (praedestinatio ex praevisa fide). For the Reformed Church, however, including the English Church under Edward VI and Elizabeth I, the doctrine of predestination was an identify marker.

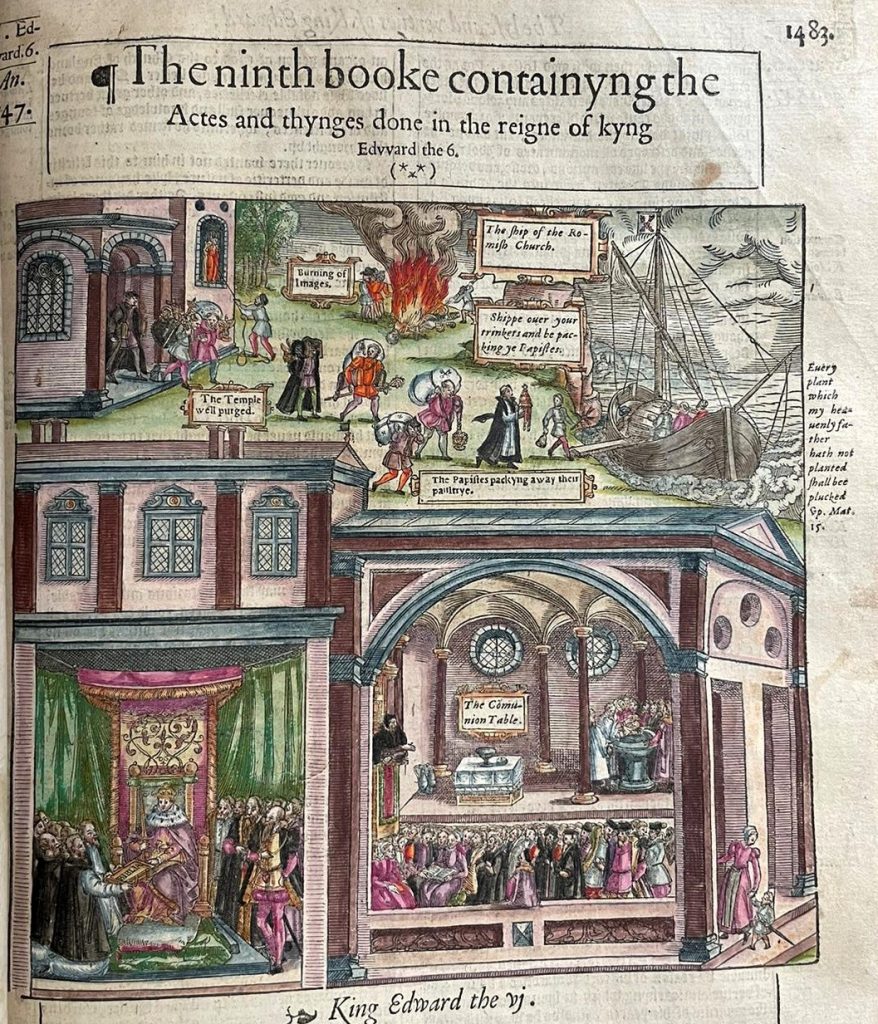

On Tuesday, the Reformed identity was examined from a different perspective. The Reformed had their own special characteristics, not only in their theological convictions, but also in their religious mentality. In his morning lecture, Bruce Gordon (Yale University) discussed the Reformed memory of martyrdom, focusing particularly on how the Marian persecutions were processed in Elizabethan Protestantism and in John Foxe’s “Book of Martyrs” (Acts and Monuments). In the afternoon, the group examined Foxe’s preface and three martyrdom accounts: Patrick Hamilton, William Tyndale, and John Rogers. Analyzing the language revealed the guiding ideas of martyrdom, which played a special role for Reformed Christians in the 16th century due to persecution in many European countries.

A page from John Foxe’s “Acts and Monuments”

depicting the changes under Edward VI

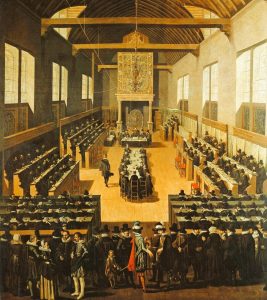

In the evening, art historian Prof. Aleksandra Lipińska of the University of Cologne gave a fascinating two-hour-plus overview of Protestant church architecture in the 16th and early 17th centuries. While all branches of the Reformation continued to use existing church buildings wherever possible, they redesigned them to a greater or lesser extent in line with the changed nature of worship. However, from the 1540s onward, new buildings were constructed that took greater account of the requirements of Protestant worship. Different architectural styles were used and combined. Alongside new Renaissance-inspired designs, there were revivals of late medieval forms and borrowings from Roman Catholic models. Amsterdam’s expansion, which required the construction of numerous new church buildings, reveals a surprising variety of Reformed churches.

Saint Pierre-le-Jeune, Strasbourg

Lutheran church that preserved its medieval interior to a large extent

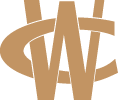

On Wednesday, the last study day, the Student Fellows had the opportunity to work on their own research projects in the Reformation Research Library. On Thursday, 2025 Research Fellow Bruce Gordon led a final work session, introducing the Student Fellows to Reformed confessions and Heinrich Bullinger’s significance for the Reformed confessional church in the morning lecture. In the afternoon, the source study focused on the Second Helvetic Confession (Confessio Helvetica posterior). This text summarizes the state of the Swiss Reformation around 1560 and illustrates the significance of the Zurich Reformation for the Elizabethan Settlement.

On Friday, Rev. Fabian Mederacke from the Evangelical Church of Wittenberg visited the summer course and discussed the current state of the church in Wittenberg. A final source study compared the Consensus Tigurinus (1549), Cranmer’s “Defense of the True and Catholic Doctrine of the Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Our Savior Christ” (1550), and Melanchthon’s commentary on Colossians 3:1–2 (1559). The group examined the connection between Christology and the understanding of the Lord’s Supper, as well as the differences and similarities between Calvin, Bullinger, Cranmer, and Melanchthon. The 1550s emerged as a pivotal decade of clarification and division. Led by Cranmer, the English Reformation church sided with the Zurich and Geneva Reformation, while the Wittenberg Reformation followed Luther. In the evening, the group met for a farewell dinner attended by Prof. Robert Kolb who had participated in the working sessions over the previous weeks and shared his insights on Luther and post-Reformation Lutheranism.

On Saturday morning, the group met one last time, and Ashley Null summarized the course’s results. Over the course of four weeks, the dense web of connections between the continental Reformation and the Reformation in England was uncovered. The ties between Zurich and Strasbourg were particularly strong. It was made clear that theological insight was a key factor in the ecclesiastical changes of the sixteenth century, and that the English Reformation Church aligned itself with the Reformed Church in many respects. This influence persisted over the centuries but also evolved and was interpreted in various ways. Today, historical research can perceive the Reformed heritage of English Protestantism objectively and appreciate its significance for early modern England.