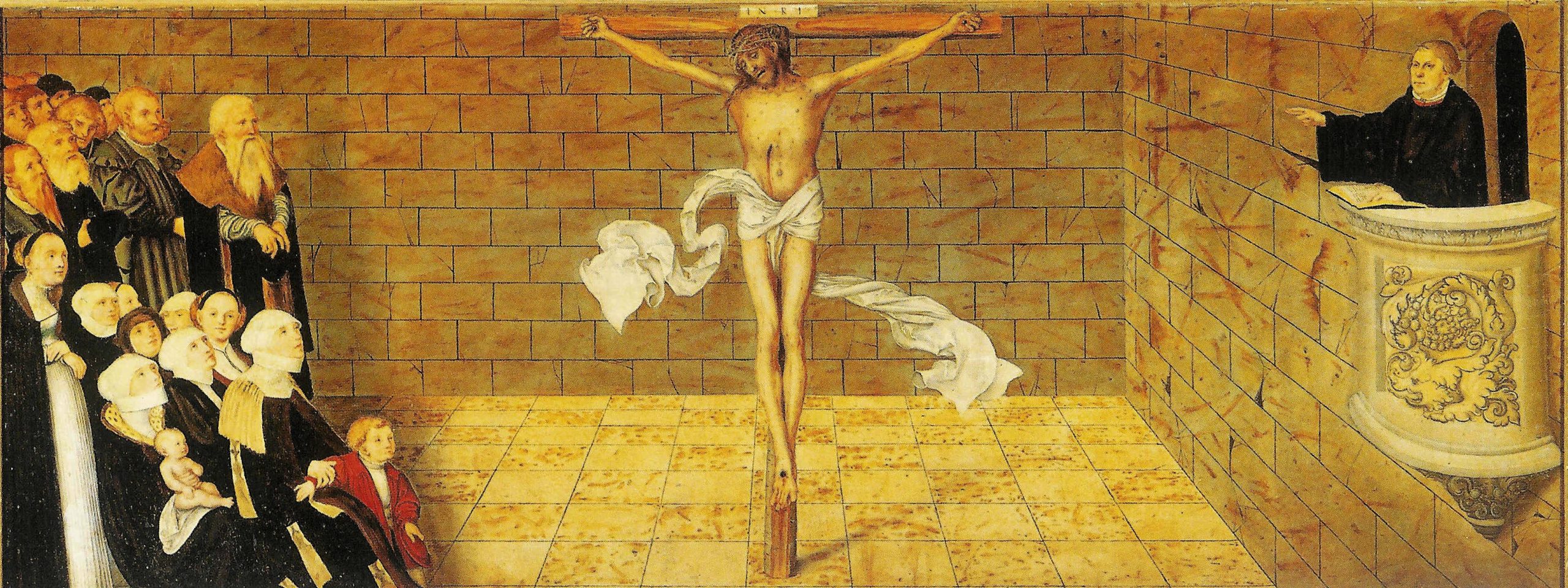

In his Invocavit sermons in March 1522, Luther said the following about the changes forced by the radical reformers in the Wittenberg parish during his stay at the Wartburg:

“Summa summarum: I want to preach it, I want to say it, I want to write it – but I do not want to compel or press anyone by force. For faith wants to convince voluntarily and without coercion. Take me as an example. I have fought indulgences and all papists, but without force; I have interpreted, preached and written God’s word alone, otherwise I have done nothing. This word did so much to make the papacy so weak that ever a prince or emperor did so much harm to it, while I slept or drank Wittenberg beer with my Philip and Amsdorf. I have done nothing, the word has directed and accomplished it all.” (WA 10/3:18,10–19,3)

The image Luther uses to illustrate his trust in God’s powerful presence in the world is a fine example of his art of preaching. He paints an everyday scene before the eyes of his audience: Luther, Melanchthon and Amsdorff drinking Wittenberg beer together while the word of God overthrows the anti-Christian papacy.

The drinking of beer is not a randomly chosen example, but it has a theological significance. It brings the divine work through the Gospel into connection with a seemingly profane, everyday event. This event, precisely because of its ordinariness and profanity, is singled out as the only right way of relating to the divine action in history: It is not people who make the Reformation and who drive ecclesiastical renewal – God alone does that. People’s task is to do what God asks them to do and otherwise just let God do his work. By sleeping or drinking their beer, they allow God to work and show that they have understood that what matters is not them, but God alone.

Similarly, Luther interprets the third commandment of the Decalogue in the sermon On Good Works: Along with faith (first commandment) and the practice of piety (second commandment), the third aspect of the relationship with God is the inner Sabbath rest and the renunciation of one’s own acting. This is precisely what is meant by beer-drinking in the Invocavit sermons. One could say: beer-drinking is a form of observance of the third commandment. What sounds like a theological tastelessness or a groundless exaggeration corresponds to an important concern of the Reformation: The Christian faith frees believers to live in this world; it takes away all religious pressure to perform and lets them live simply as creatures.

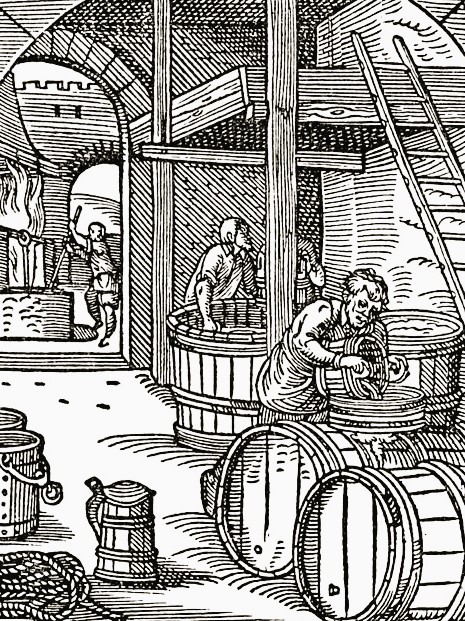

The fact that beer in particular is an example of faith-based life in the here and now cannot be surprising if one knows about the importance of beer for everyday life in the early modern era. In pre-modern times, drinking water supply was a problem in cities. Since there was no separate sewage system, all running water and wells were contaminated with germs and their water could not be drunk without precautionary measures. Moreover, people preferred to drink something with taste and nutritional value rather than simple water. That is why beer and wine were widely used as everyday drinks consumed in large quantities. The beer was mostly low-alcohol beer, so that even children and young people could drink it. In addition, there was a wide variety of stronger types of beer, rich in nutrients and alcohol. Brewing was often done at home. In larger households, such as the Black Monastery in Wittenberg, large quantities of different types of beer were produced and stored in barrels or bottles under the guidance of Luther’s wife Katherine.

Beer was not only an everyday beverage, but also a remedy. Luther, who suffered from constipation, knew about the laxative effect of beer from the nearby city of Naumburg. To his colleague Justus Jonas, who suffered from kidney stones, he recommended Wittenberg beer, which particularly stimulated the flow of urine. Even more importantly, beer also served as a stimulant. This applied less to the everyday low-alcohol beer than to the strong beers, which offered a wide variety of different tastes depending on their origin and brewing method. Luther was probably thinking of such enjoyable beer-drinking when he gave his example in the second Invocavit sermon.

Of course, Luther also knew that people in Germany liked to overdo it with alcohol:

“Our German devil will be a good wineskin and must be called ‘Boozer’, who is so thirsty and weary, that he cannot be refreshed with such great drinking of wine and beer. Such eternal thirst will remain Germany’s plague (I am worried) until Judgment Day.” (WA 51:257,6–10)

Luther could sharply criticize that some people got drunk like swine and behaved as if they had been created by God as beer bottles. However, this apparent abuse did not cancel out the right use. God had created beer for the “nourishment of the body” and therefore there was nothing wrong with moderate beer consumption. Luther attached great importance to always having good beer to drink. When he once came across bad beer during a stay in Dessau, he wrote to his wife in Wittenberg:

“Yesterday I got a spoiled drink, so I had to sing: ‘Oh, I don’t drink well, I’m so sorry’, and I’d so like to have something good to drink. I thought of how good wine and beer I have at home, plus a beautiful wife – or I should better say: a master. You would do well to send over my full wine cellar and a bottle of your beer as soon as possible, otherwise I will perish from the freshly brewed beer here.” (WA.Br 7:91,7–12, no. 2130)

And it was precisely because of this presence of beer in his everyday life that drinking beer for him became a symbol of Christian trust in God. This is especially true in comparison with wine. Luther knew well that wine was the actual theological beverage and beer was something purely of this world:

“Wine is blessed as is attested in the Bible; beer is only a human tradition.” (“Vinum est benedictum et habet testimonium in scriptura, cerevisia autem est traditio humana.”) (WA.TR 1, no. 254)

However, precisely because of that beer could serve to make clear that when God is active humans have to stay passive.

With his beer example Luther proves that it is not human willing and running that matters before God, but that one is allowed to entrust oneself to God’s care. He proves that faith does not demand that we turn away from the world and lead some elitist existence, but that faith enables us to participate in this world’s life. He proves that humans do not need to let themselves be infected by the world’s striving for performance-based identity, but can rejoice in what was given to them by God. A person who is at peace with God, with the world and with himself through faith in Christ simply enjoys his beer (or any other everyday food):

“If you have nothing or little from yourself, look to the treasure that God gives you through his Son. Hold fast to it and say, ‘This is certain […] through the Word and Sacrament, that I have not riches which the world admires, but riches of eternal salvation and life […].ʼ When you recognize this treasure, you will be satisfied and say: ‘I may not have gold, money, castles or worldly power, but I have the Word, baptism, the Son of Godʼ etc. What do you lack? That your belly may not be full? No, your belly will be as full as the emperor’s. It is certain that a drink of beer tastes better to you and is better for you than the emperor’s delicious malvasia wine.” (WA 49:625,1–9)

Further reading

- Adolf Allwohn, Luther und der Alkohol, Berlin 1929

- Beatrice Frank, Martin Luther und das Bier (Jahrbuch der Gesellschaft für die Geschichte und Bibliographie des Brauwesens 1996, 31–37)

- Martin Luther und der Wein. Aus Tischreden, Briefen und Predigten, ed. by Christine Reizig and Gunter Müller, Dößel 2001

- Wolfgang Dieter Speckmann, Ein großer Geist mit eigenem Bier. Philipp Melanchthon (Jahrbuch der Gesellschaft für die Geschichte und Bibliographie des Brauwesens 1997, 13–21)

- B. Ann Tlusty, Bacchus and Civic Order: The Culture of Drink in Early Modern Germany, Charlottesville 2001